Are You Still Watching?

2015 - 2020

I’ve spoken a little in my last two posts about what came next in my work. It’s a thread I followed for a long time, so this one will be about everything I did from 2015 up to the pandemic, and it’s going to be long. It’s a reflection written with the benefit of distance. It’s taken a long time to reach this point, and I want to tell it properly, so... buckle up, I guess.

---

I was really into Father John Misty at the start of the 2010s. The album Fear Fun was lush, absurd, and sharply self-aware. I liked how Josh Tillman spoke in Interview magazine. For context, it’s about the idea of alter-ego and the difference between his older solo work, under the name J. Tillman, and his new Father John Misty name. It’s basically the mask quote from The Picture of Dorian Gray for the Pitchfork generation, a knowingly artificial persona that somehow made space for deeper honesty.

“It’s a mask. I know that’s a loaded word for people and it implies that I’m lying, but I’m trying to be forthright about the fact that these personas give me a foil. Here’s this bizarre mask. Now I’m going to give you everything about me.”

I have always felt that I live one step removed from the person I am inside my own head, like a puppeteer operating a marionette around the workplace and the supermarket and the pub. I know now that this behaviour is literally called masking, and it’s a survival tactic, one that has allowed me to fly under the radar. It’s the reason I’ve always felt like a secret agent reporting my observations back to the head office inside my brain. It’s the eye that observes the people around me and copies them. It’s the way I code-switch depending on who I’m speaking to. It’s how much I choose to let my estuary accent come through. It’s the constant inner voice that coaches me through every interaction. We have to make eye contact now. No, that’s too much. Don’t answer ‘how are you?’ honestly, remember - it’s a script, not a question. Don’t forget to ask questions back. Try to say something funny but don’t try too hard. Oh, shit, they’ve said something sad. Do the sad face. Fuck, am I doing it right?

When I get it wrong, I can feel the red subtraction symbols appearing above my head like a Sim.

Of course I was drawn to the idea of telling the truth through a mask - it made intuitive sense to me.

As I built my ~*~Instagram identity~*~, the barricade between me and the comments and likes, it struck me that, actually, it was the most honest thing I could do. A lot was said, at the time, about the dangerous artifice of social media, but I felt it was only as fake as the construction of identity in the ‘real’ world already was. Why keep trying to be ‘myself’, when that self was only ever an echo anyway, a reactive reflection of whatever space I occupied? Why not step into the mirror and embrace the hollow flatness of objecthood? Its honesty was in its inauthenticity, because I felt like an inauthentic empty vessel all the time anyway.

One of my favourite pieces of writing on this subject - Hito Steyerl’s A Thing Like You and Me, became a core point of reference for the work I started to develop. It became about a kind of voluntary objecthood. I called it ‘responding to the predicament of being seen’.

I read Baudrillard and Goffman and Haraway and Braidotti and more in between. I referred back to this interview with Kate Durbin and this conversation between Jesse Darling, Molly Soda and Rosemary Kirton. I chose ways to contextualise what I was doing, but I still struggled to pin down my own position. Which target was I aiming for?

I do like theory and thinking about things, but often it felt a bit forced. I wanted to leave all the questions open. I didn’t necessarily want clarity of purpose. I had an inkling then that art degrees - so often seen as indulgent or unnecessary because they rarely lead to lucrative careers - are expected to justify themselves academically this way, find ways to prove it’s a valid discipline, worthy of a place in institutions increasingly biased toward STEM subjects. Learning that language was another form of masking, a way to pass.

The work got questioned in relation to feminism a lot, of course it did. That was an important critical lens to view it through. It was a conversation I couldn’t detach the work from, because of who I am and the body I inhabit… but I didn’t have easy answers to questions about whether the work was feminist or not, or if auto-objectification - mimicking the Big Bad Thing - was damaging to women. I wasn’t even sure I felt like a human being.

I was taking the things I had learned to use to perform personhood and making them look as uncomfortable as they had always felt. That discomfort was already in conversation with systems of gender performance in many ways, but I wasn’t trying to make a feminist stand. I was only trying to visualise the fragmentation I felt. The questions that came out of that were just signs the work provoked discussion. That felt like enough.

---

2015

The first images I made and posted to Instagram that felt like ‘pieces’ that could stand alone, instead of only working as part of a continuous feed, were the three below. Probably because this was the first time I used body paint. It didn’t feel like a picture of me. These were posted to Instagram but they also became prints, bringing them back into the physical plane. I liked to send images on a journey into the virtual and back again, flickering between presences.

Josh Tillman again: “Part of the problem with searching for realness, and there is some searching involved, is that you have to just end up back where you started. There’s no glory. You think you’re going to be a conquering hero or something, but you just have to be able to live with the cosmic joke that, at the end of it, you just get to be yourself.”

I liked exploring the idea of the ‘loop’ in relation to all this too, having previously been a very serious teenager who listened to Okkervil River and read The Unbearable Lightness of Being. I thought about circularity and return so much that I got a circle tattooed on my arm. It seemed to sum up the whole mess of life. The heaviest weight, the clumsiest shape.

This thinking led to incorporating elements of repeated movement in the images, so they existed as seconds-long videos with still and moving parts - like cinemagraphs - that played on loop.

I took my face and mapped it onto a Cinema 4D generated metaball to make this video, which was shown in The New Flesh at VIVO Media Arts Centre in Vancouver, part of 2015’s The Wrong Biennale.

I also started to play with livestreaming around this time, all facilitated through the connections I’d made with other artists online. It’s rough, sketchy, studenty stuff, but it was a phase worth mentioning. They were erratic experiments fuelled by a deep need to stay visible.

The first was an overnight live show I did from my living room in Manchester in front of a green screen curtain, where I made a sponge cake and some blob sculptures on camera. Psychedelic live backgrounds were provided by Fever Dream Interactive, and this feed was projected onto a white dome cake at an event at The Moon in Grand Rapids, Michigan, so I could be consumed, too.

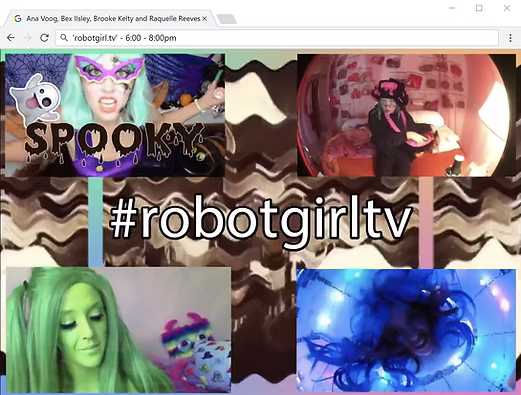

There was also a short-lived stint I did with a collective - ROBOTGIRL.TV, formed by internet legend Ana Voog, along with artists Raquelle Jac and Brooke Kelty. I’d applied to work with Dean Brierley of Caustic Coastal through a university programme in early 2016, and he curated a show of student work from successful applicants in a hotel room at the Manchester Britannia. ROBOTGIRL.TV streamed a Google Hangout - entitled ‘Room Service’ - from our respective homes to the TV in the room, and we invited people to call us on my phone. I’d been reading Theresa Senft and looking at work by people like Leah Schrager. I was thinking about erotic labour, about what camgirls do. What people do in hotel rooms. I was wearing a black dress in the bath. I didn’t yet have the tools to handle the vulnerability it demanded. I panicked immediately after, overwhelmed and humiliated in cold bathwater, ruminating all the mistakes, as if every minor stumble was a public failure, as if every misstep was The End - the cost of showing myself without the mask.

---

2016

I took @bexilsley to Madrid with my student loan, inspired by Juno Calypso’s body of work The Honeymoon, which I adored. I stayed overnight in the Silken Puerta America hotel and took pictures of myself on the floors designed by Zaha Hadid and Plasma Studio, wearing LED wings. I wanted to look like the past’s dream of a lonely and sterile future, some spirit left over after the mass-upload, still plugged into the hub.

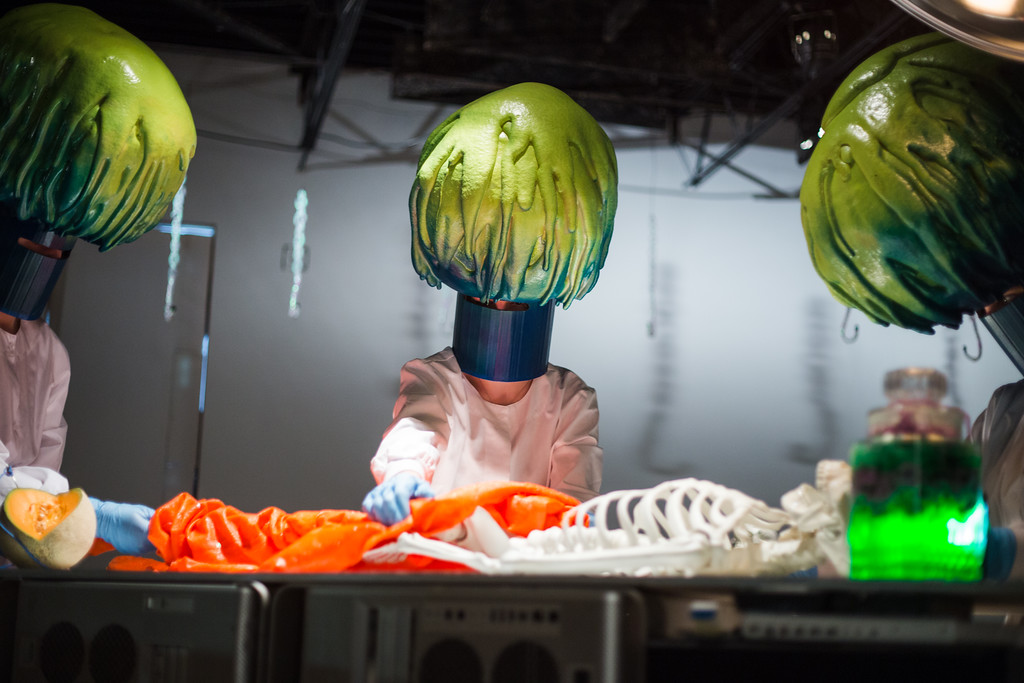

Before the end of my third year at art school, I was invited by my friend, professor Natalie Wetzel, to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to work with students at KCAD, give a talk, make a video based on an illustration from Luigi Serafini’s Codex Seraphinianus with Bokeh Monster. I met Natalie through the Flaming Lips extended universe. This was such an amazing opportunity, I couldn’t believe I was being paid to do something like that when I was still a student myself. I still think back on it as one of the best weeks of my life.

I remember being quizzed on arrival in the USA by a border officer about why I was travelling. He googled me during the interview and asked me what my parents thought of me being topless on the internet. I told him I didn’t care. Moments like that reminded me how thin the line could be between being perceived as empowered and being seen as exposed.

At KCAD, I had the opportunity to have my head captured in three dimensions with an Artec Eva 3D light scanner, because Natalie liked to create busts of every visiting artist. I went home with a digital 3D copy of myself. I used Meshmixer to carve up the .obj file and turn it into a proper mask of my own face, which I then had 3D printed at MMU. I mounted it on an acrylic disc with floating hemispheres which could be hair, or ears, or something else.

I used this piece for my degree show, marking the end of my time at university. I created a VR environment in Unity using the same mask file. The final piece was this virtual-reality space, viewed on a phone with a Gear VR headset, and the wall-mounted mask piece, accented by neon strip lights.

I submitted this to the Woon Prize in 2016, along with the Telepresences videos and prints from the hotel photos. To my astonishment, I was shortlisted and I came third. I won £6000 and spent some of it on a new top-of-the-range camera, lenses and tripod, since I wouldn’t have access to those through uni anymore. The rest went on new work, rent, and living costs. Christine Borland, who was on the judging panel that year, commented that she saw my work as sculptural, because I had made myself the sculptural object. That - as well as seeing one of my best friends win the first prize fellowship on the same night - made me so happy during a time that things in my life outside of artmaking were pretty much all tumultuous and horrid.

It might feel like a tonal pivot to dip back into the darker parts here, but in the few years after university, I was struggling and dysregulated, a state that shaped how I moved through the world, both socially and professionally. I was burnt out but still trying to commit to every show and submit lots of applications, because it was all I felt I had. I was abysmally skint and my living situation was less than ideal. I was in a constant state of urgency, back and forth between the South, the North and the Midlands, flailing with family problems, self-esteem issues and no permanent address. I had to think of ways to keep going, despite it all, out in the real world.

In the summer of 2016 after I graduated, I moved to Liverpool and started working at a jeweller, up in the cash office. I was invited to make something for Platform Projects’ Recent Graduates booths at the Affordable Art Fair in London. We had some meetings. They liked the performance-related aspects of my practice, and we agreed I’d stage a live-streamed performance from my box room in a 9-bed shared house in Toxteth to a booth at the fair in Battersea.

We were plagued by logistical difficulties, problems with equipment rental, all compounded by me being so far from the site and not being able to travel easily (work, money). My stream was projected into the booth and there was an iPad so people could message me directly through Facebook messenger. I’d type back and react on screen to whatever they said. I said I would talk to anyone about anything they wanted. I streamed for 37.5 hours across 5 days, only breaking to go to the toilet. It was a lot. The concept came together quickly, and wasn’t as sharp as I’d hoped, but I was so, so afraid to lose momentum, let people down, or squander these great post-university opportunities I’d been offered. I constantly pushed myself beyond my capacity, then crumbled in private. I thought that’s what it took to succeed.

2017

ROBOTGIRL.TV streamed together once more - a 2-hour conversation shown live at the launch for the first issue of isthisit? magazine. It was just an honest conversation between friends, a public catch-up, not a performance. I think, for me, it was about what it could be like to live in public, as my collaborator Ana Voog had done in the past with Anacam. What would it feel like to put everything out there without any shame? I was in my dad’s living room, having moved back to my birthplace in Kent from Liverpool in the wake of a traumatic break-up. I was in a very fragile state, following a year of emotional abuse from an ex-partner. Some shame wouldn’t have gone amiss, looking back now. Perhaps I wish I’d had a clearer sense of when I was performing and when I was just exposing something too raw to protect. I mistook openness for fearlessness. I blurred the lines between courage and leakage. Not every idea was a winner.

I was unable to find work in Gravesend that would have allowed me to move out of my Dad’s flat and live anywhere near my hometown, so in May of 2017, I went back to Manchester and took a friend’s spare room. I got a job working for a wholesale handbag company in Cheetham Hill. I had to come up with female names for each handbag style, so I bought a book of baby name ideas from Amazon. I joked that it was the most spinstery thing I’d ever done.

I’d been offered my first solo show - I called it ‘Emotional Processing’ - in Warrington. I had two months to make something for it.

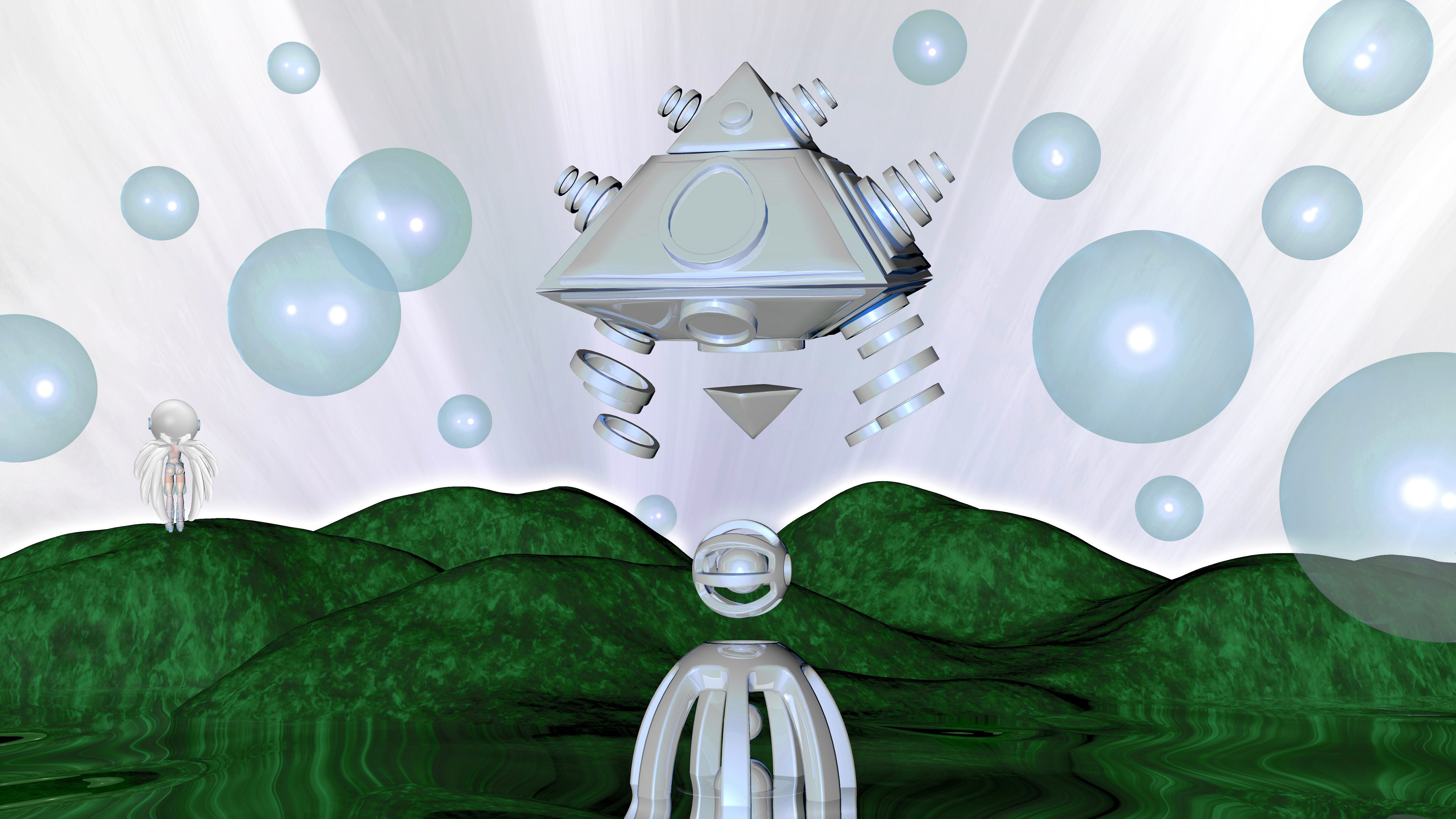

While I was in Kent, I’d been making Y2K / rave flyer inspired 3D worlds (one was with Neon Saltwater, whose work I love so much). They were all acid gradients and plastic gloss...

...but I missed working with physical things, so I did what any totally sane person would do, and I wrote to someone on the board of directors of a property development firm, on pastel children’s stationery. I introduced myself and asked if there were any unused spaces under development that I could move into for a couple of months to make artworks. Somehow, this worked, and I gained access to an entire empty railway arch in what would become Depot Mayfield.

I made video works and displayed them on screens that were part of larger pieces assembled from various existing objects and custom-made parts. The response from visitors was lukewarm, but I understood why. Perhaps I hadn’t fully considered how it might land in that space. Even partial readymades are still a hard sell.

I still like two of the four.

‘Character Building’, above, began with an MDF base and two bent metal tubes I designed to mimic a ladder from a type of playground climbing frame. I added mannequin legs and a TV with a built-in DVD player, which showed a looped video of the same mask from the 2016 degree show piece.

‘The Heaviest Weight’ was a wall-based piece consisting of print I’d made from an old photo of ink, oil, and milk, affixed to a Perspex disc. I attached a painted mannequin arm to that, which could hold an iPad playing a video of my face, as if I was trapped in the device. A kids’ hula hoop acted as a frame, along with a painted model of serotonin’s molecular structure.

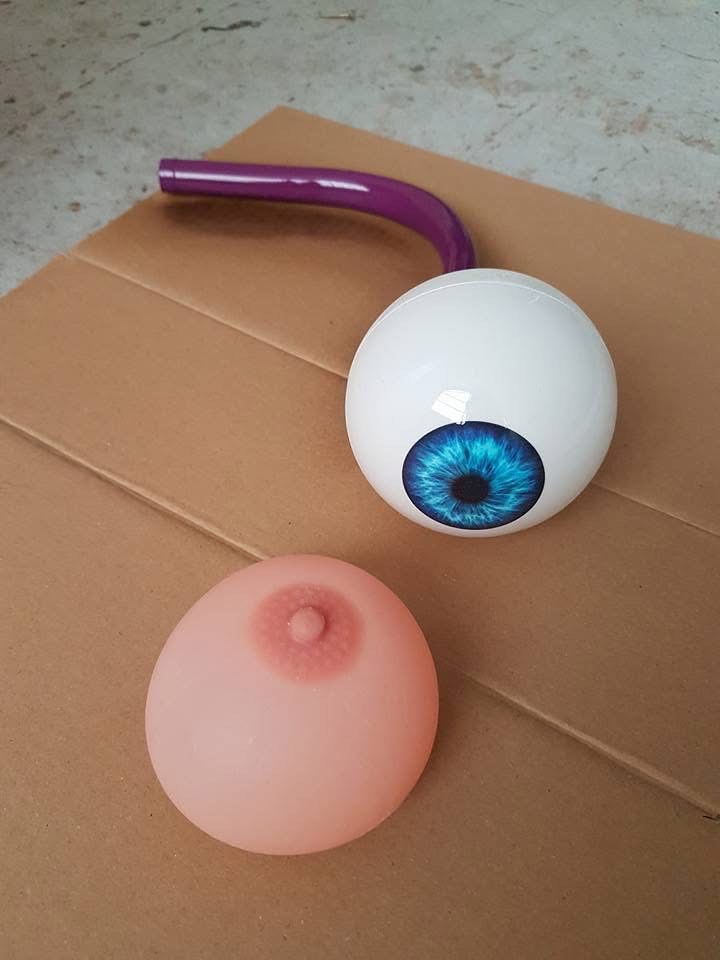

I also ripped out the bed of a trampoline and replaced it with a mirror. I mounted a nail technician’s training hand on the handlebar to hold a selfie stick, which cradled a phone playing another face video. I made a table by painting a plinth and placing a lazy susan on top of it, with a novelty stress ball in the shape of a tit and a pipe with an eyeball attached to it. Not my favourite, but I liked its spinny absurdity. I’d still use it as a table.

I tried to frame it all with an overwritten statement, of course. At the time, I said this:

‘Emotional Processing’ refers to processing as a computing term, a nod to our lives as data, the mediation of intimacy, vulnerability within a superficial feedback loop. It also refers to watching my own internal responses to trauma and anxiety. It’s the body torn up and mangled by commodification, commercial colour palettes, screens and mirrors, self-conscious looking.

I use looped video and circles because the search for personhood feels, to me, circular. Some of the playfulness refers to a temptation towards regression. We live in a simulated, simplified world. Perhaps debates about authenticity are useless now. What parts of us are new, and what parts have always been? Which cycles can be broken?

---

By August 2017, I was living in a tiny room near Strangeways prison that only locked from the outside, with a creepy landlord who wrote me unsettling poems when I helped him edit pictures of workwear for his website. When I viewed the place, there were several people living there. A week later, they had all mysteriously vanished so it was just me and this one guy who owned the house. I didn’t feel safe there. Then, there was a death in my family, which was my breaking point. I couldn’t outrun fear and burnout layered with grief. I packed everything in and went to live in Leamington Spa with my mum. Yet another new start.

---

2018

I started a temp job at Warwickshire County Council, scanning old social services files (amazing job for the nosy) and I finally had enough income to rent a proper studio space at Meter Room in Coventry. I began working towards my second solo show - boom + bust - at Goldtapped in Newcastle’s Newbridge Project.

Being back at my mum’s house in my twenties, spending more time with family (my young half-sister in particular), started to raise questions for me about why things had gone the way they had.

I drew comparisons between the inevitability of generational trauma, inherited through genetic code, and, as Mark Fisher described in Capitalist Realism, the widespread belief that capitalism is the only viable economic system in a cultural atmosphere so saturated by neoliberalism that even imagining an alternative feels futile.

I thought about living in a world where we’ve internalised the idea that change isn’t possible, where any meaningful sense of agency has been reduced to regressive aesthetic gestures. I pictured an unbroken, fluctuating wave through time - unstoppable turbulence I felt powerless against.

I painted a red line on the gallery walls like a sine wave. It was a way of saying that emotional volatility can feel as inevitable as the rises and crashes of the markets, and equally outside our control.

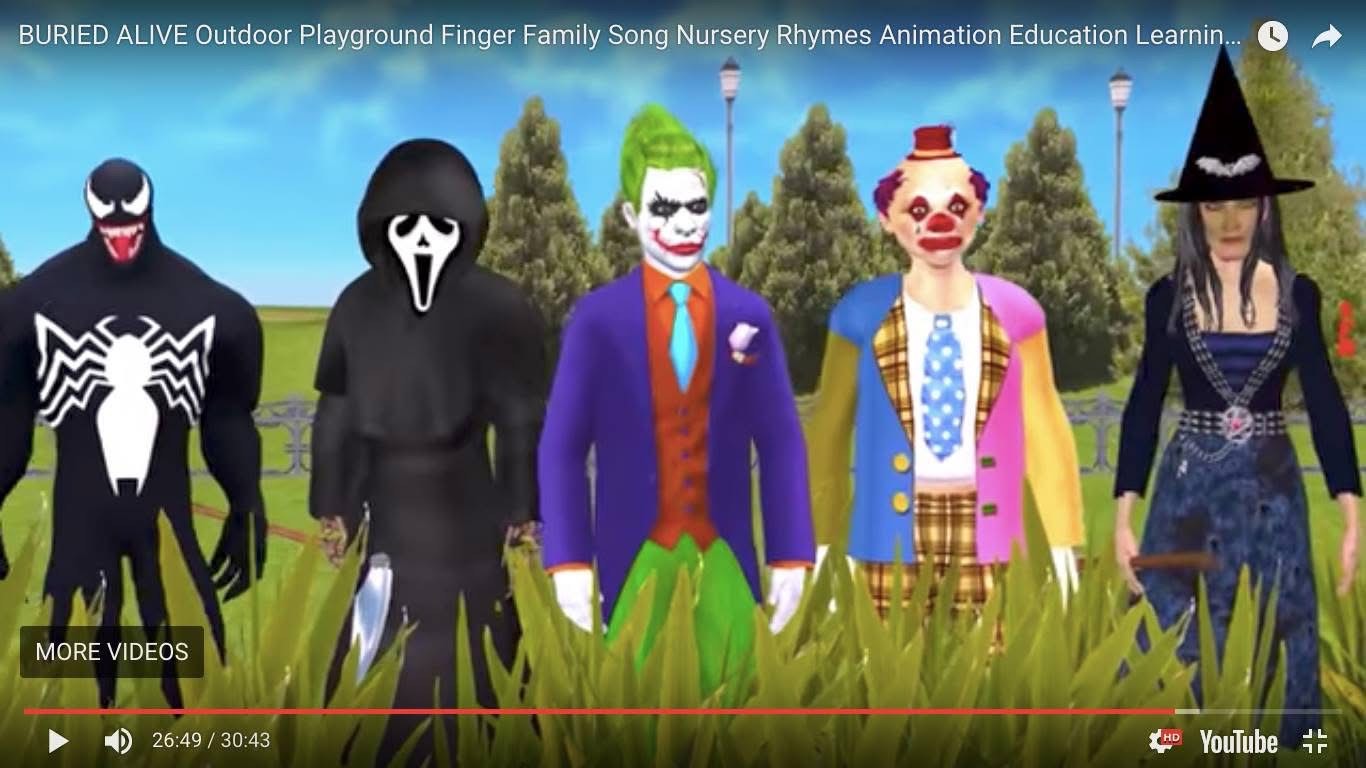

I’d also gone down a deep Youtube rabbit-hole of so-called ‘Elsagate’ videos, off the back of James Bridle’s essay Something is wrong on the internet. It describes how YouTube’s kids' content ecosystem had become a grotesque feedback loop, churning out disturbing, nonsensical nursery-rhyme videos, many of them detached from intention or authorship.

Bridle's point was about the systems that facilitated this flood of weird bot-generated content. How algorithms produce monetised slop at scale, designed to keep us watching, regurgitating our worst tendencies, and flattening them into marketable fragments. He called it “infrastructural violence”.

I made my own ‘Finger Family’ video. Me in a latex bodysuit with inflated cartoonish breasts, each fingertip replaced with a miniature version of my own head.

It wasn’t satire so much as a weary surrender to the pile, a replication of the genre, a gesture towards collapse.

Bridle: “This is content production in the age of algorithmic discovery - even if you’re a human, you have to end up impersonating the machine.”

I also made lightbox portraits of myself as this character, and of my ten year old sister, wearing the same outfit. If her image disturbs you, that was the point. Where’s the line between innocence, mimicry, and complicity? What are we doing to young brains when we give them iPads? I’d been thinking about that since I saw her try to scroll down on a paperback with her finger at age two.

The centrepiece was a playground swing I’d made - Mood Swing. I replaced the seat with a mirrored metal sphere on a chain. It was a half-nod back to Miley’s wrecking ball, a joke about our old connection, but she was also a woman mid-meltdown who got aestheticised into a meme.

---

2019

I stayed temping at the local council and making work at Meter Room when I could. I moved out of my mum’s place. I joined Birmingham’s Black Hole Club at Vivid Projects so I could find fresh creative connections in a different scene. I participated in 2019’s Coventry Biennial. All of this was still difficult in places, I still had time and energy constraints, but life was stabilising. My third solo show - SPLITS - at Odox, Birmingham, was scheduled for June.

The first thing I made was this image (left), splitting myself into colourful facets - self-mythology as parts of a whole. I saw them like a warped team of post-transformation magical girls from a shoujo manga, like if the Sailor Senshi were all phone-addicted. Sailor Moon (right) was one of my first hardcore special interests, at age 11. I spent my lunchtimes at primary school copying Naoko Takeuchi’s drawings and teaching myself Japanese instead of playing outside with other kids. This one got printed up onto fabric, something like a wall hanging in a fan’s bedroom, like something I would have worshipped as a kid.

I made a video called Compassionate Other. The audio track was an AI voice reading the transcript of a bizarre CFT exercise I had to do in therapy (recorded in secret). I thought the exercise was a bit silly at the time, but, I also recognised that I had been othering myself to process things for... well, quite some time. I thought about the potential there was for artificial intelligences to become a form of therapist in the near future, and whether that felt unnerving or not. It brushed up against my own attempts to turn myself into a cipher, a space for service. Can AI help shame-filled people to love themselves?

I made some more loops to be shown on screens, and some more body objects. I named the ball-jointed doll legs in the birdcage ‘Hansel’, just for myself, after a stunningly 1980s clock tower in my childhood home town which used to play a disturbing mechanical Hansel and Gretel show every hour back in the 90s. The Hansel figure would sit with his legs dangling out of a cage much like this one, while Gretel swiftly pushed the witch into a tiny oven in one jerky, robotic lurch. You could see the witch’s little feet kicking. I loved that fucking clock.

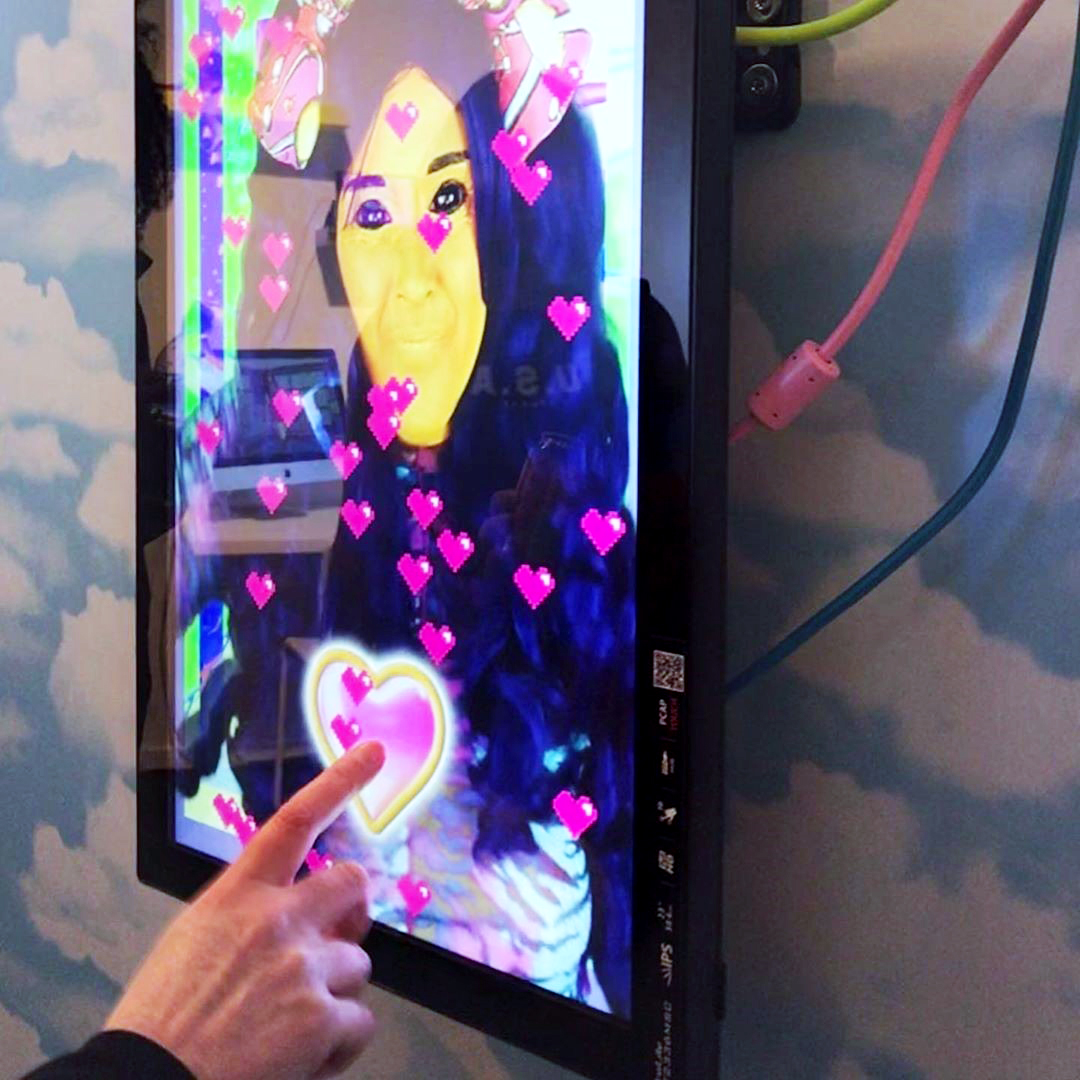

The piece I liked the most (by far) was a touchscreen-interactive video I made with the help of a relative in the games industry.

I’d filmed a video of myself (4 minutes, 44 seconds) as one of these character facets. Over the course of the video, I smile, I dance, I wave, I check you’re still watching, I tap on the glass, I grow more desperate, I hit myself in the head and I scream and I fall to the floor. The soundtrack is a layered cacophony of retro midi music and arcade coin sounds.

The video was split into many seconds-long clips. The only way you could watch the full video in one smooth sequence, without it glitching out and going back to the start (a ‘press play’ prompt screen), was by repeatedly tapping a big heart-shaped ‘like’ button as fast as you could. The repetitive tapping was meant to start aching by the end of the sequence.

It’s a familiar statement about social media, but I really loved how I’d made it. I still do! I bought a 23” Iiyama touch monitor to show it on. The work was compiled onto a single connected computer. I called it ‘Are You Still Watching?’, like the message you see when you binge too many episodes on Netflix.

2020

Do you have a favourite art gallery? I do. Annka Kultys Gallery has a habit of showing work I really, really love. I am such a big Signe Pierce fan. It was the first place I saw Molly Soda’s work in a real-life setting. AKG has always supported the kind of forward-thinking, technology-focused work that really resonates with someone like me.

When I was offered a week-long show at Annka Kultys Gallery as part of CACOTOPIA 04, it felt like an arrival at the apex, like the climax of the story, because secretly, showing there was my ultimate goal, like, the fantasy goal. It would be a proper sign I had Made It. I used to think the same about living in a semi-detached house with a round window when I was a kid (so I could pretend I was on a boat). Now it was happening. It happened. I was thrilled.

Because life is life, I fell over in the shower and broke my arm, so I couldn’t go to the opening.

---

The End

When I came out of surgery with bones bolted together and my arm in a cast, I went down to AKG to see my show and pick up some unused work. I arrived to find that the only existing build of ‘Are You Still Watching?’ was no more. Something had happened to the computer, and it wouldn’t turn on. The screen was black and a single red light blinked at me from the tower. Since it wasn’t even my computer, I wasn’t sure what to do, so I hauled it home to Leamington and left it with the relative who owned it to take it over to a repair shop and get it assessed. That was February 2020. Guess what happened next?

Lockdown measures meant I couldn’t access the computer while it was at somebody else’s house, and that it wasn’t too easy to find a way to get the computer looked at by a professional. Time passed. I wanted to know what we were dealing with before I said anything. The pandemic wasn’t over as soon as any of us would have liked. Eventually, it felt like too much time had passed to ask AKG about the loss of my work.

Much later, I learned it was probably a power surge, so that was a lesson learned for me about surge protector bars.

I may still try to recreate that piece one day, perhaps as an app, but it doesn’t feel quite as relevant as it used to anymore, so maybe I won’t.

I’ve always had this weird thing where, if I lose the last piece of work that felt valuable to me, it’s like someone has come along with scissors and cut the thread I was holding onto, so I can’t find my way back in the dark. Losing that piece felt like being cut off from my own practice. I can’t really explain why. Nevertheless, there are silver linings to these things. Losing it, coupled with living through Covid, forced me to stop and take a break. I’d already made it to the walls of my dream gallery anyway, where else to go next, but bed?

Taking five years out has been really restorative for me. I desperately needed it. I stepped away from the constant pressure to produce and worked on laying the foundations I should have had in place before I’d tried to build upwards. I went to Glastonbury Festival. I went to Yellowstone. I played 935 blissed-out hours of Baldur’s Gate 3. I got married! We converted our upstairs spare room into a studio for me, a place to house my old things. My husband made a sign for the door.

---

Onward

I will write about the future next time, but I believe that this body of work has run its course.

The only thing left to do now, in a world that only got faster and more fractured while I was resting, is to make slow work, not terminally-online work. I can’t respond any more to a world that has already moved on by the time I’ve opened Adobe Creative Cloud. I don’t want to think about microtrends, or generative AI, or TikTok auto-scroll (okay, maybe a little, when I’m doing the washing up). That’s the reason I’m making a sequel to a 34 year old game in a forgotten language for an obsolete console (more on that later). No deadline. It’s the reason I am fucking blogging right now.

I had to exorcise all this first though. Not for pity - it’s cathartic, yes - but more than that, I want to show what it meant to be a promising young artist in the 2010s who left university with plenty of momentum, but no foundation, no savings, and no safety net. I was trying so hard to ‘emerge’ in the right way despite that, in the right spaces, without ever faltering. It’s not easy.

If you’re in that space now - broke and exhausted and trying to make something real from it - I want you to know: It’s not you. The system is rigged. You’re not failing. You are fighting. You should keep fighting, but you should remember to rest when you need to. The world will still be here when you wake up. I promise it will.

If you knew me back in the dark years, I might have seemed unreliable, erratic, hard to pin down. I know there were things I promised to do I pulled out of at the last minute. There were social situations I fumbled. I want to be honest about that. I don’t need absolution. I’m aiming for context. I had survived things I didn’t yet have language for, trying to work in shared houses where I didn’t feel comfortable enough in my own skin to even prepare food in front of other people, so I went to sleep for dinner instead - a quiet workaround for poverty and something I couldn’t yet name.

I want to go back and hug that version of me. I want to help her carry her bag. I want to tell her she was doing great. I want to tell her that she will get out and discover a safe and stable life again.

I think about how many people must fall through the cracks because they are not born into networks that teach them to believe they can belong. I think about how mental health language is weaponised. I think about how the line between ‘visionary’ and ‘liability’ is so often a question of class. I think about how we reward resilience only after it becomes palatable, when it can be folded into a good story.

I think about how many people will never be given the grace to become a good story.

You could just write your own.

B